It was very cold in London on the morning of January 30, 1649—the day King Charles I was scheduled to be beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Palace of Whitehall, following a conviction for high treason during the English Civil War. Dressing before before sunrise, the king reportedly donned an elaborately patterned “sky-coloured satten wastecoat” beneath his black garb. He didn’t want to shiver in the winter air, it’s been said. “He didn’t want people to think that he was frightened,” says Meriel Jeater, a curator at the Museum of London Docklands.

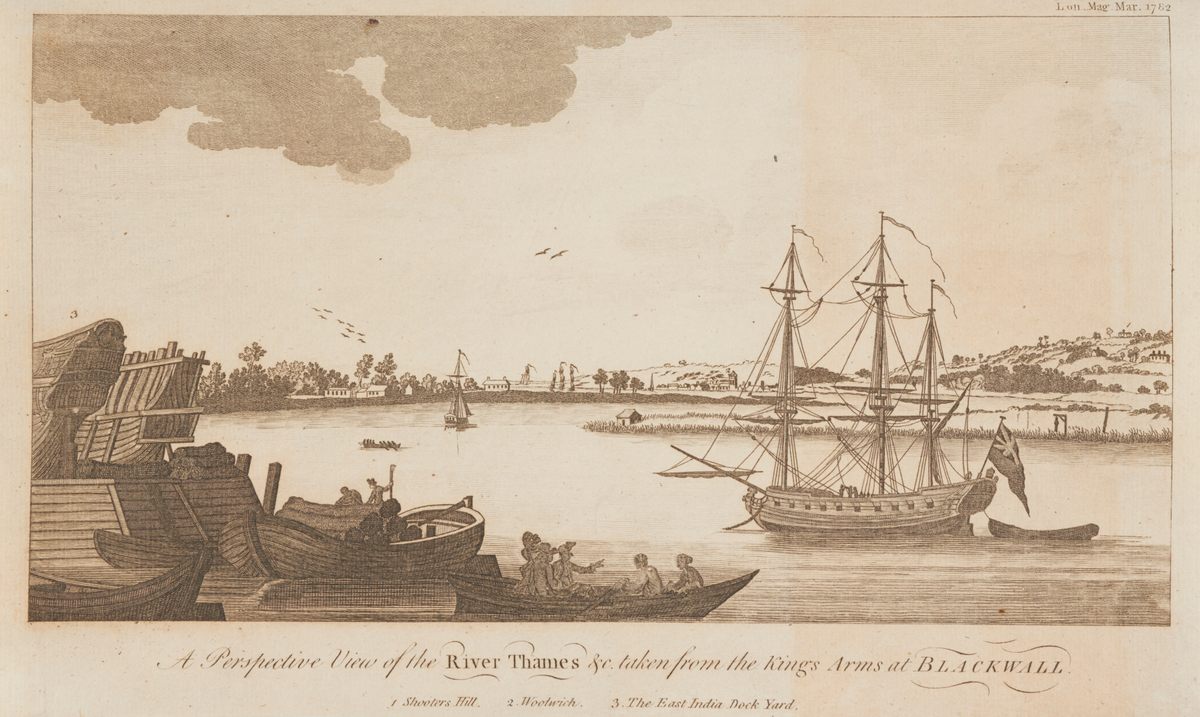

Jeater knows a lot about the king’s layers. For almost a century, the museum has had in its collection a faded and stained knitted silk waistcoat, with sleeves, that came with a note of authenticity, claiming that the doctor who attended to the king that day had taken possession of it on the scaffold after the monarch’s death. It is now on display at The Museum as part of Executions, an exhibit that explores 700 years of public executions in the British capital—from the first documented one, the hanging death of William Longbeard for sedition in 1196, through the hanging of Michael Barret for his part in a bombing in 1868. Physical reminders of these executions have been a long part of London’s landscape. “Ordinary prints of London happen to have in them pictures of gallows because they were landmarks in the city,” Jeater says. Pictured in another seemingly benign image of the River Thames in the museum’s collection is a gibbet, a dead body hanging in a cage as a reminder to others of the fate that awaited those who committed any one of 200 offenses, from theft to treason.

The museum can’t yet guarantee that this pale blue garment—meant to be worn over a shirt but under a jacket—was the one the king actually wore on the day of his death, but the exhibit includes other items said to belong to Charles I, including a handkerchief, a pair of gloves, some fragments of silk clothing. The royal raiments will be displayed alongside items belonging to ordinary people who were executed in public as evidence of the deep-rooted legacy of state-sanctioned executions.

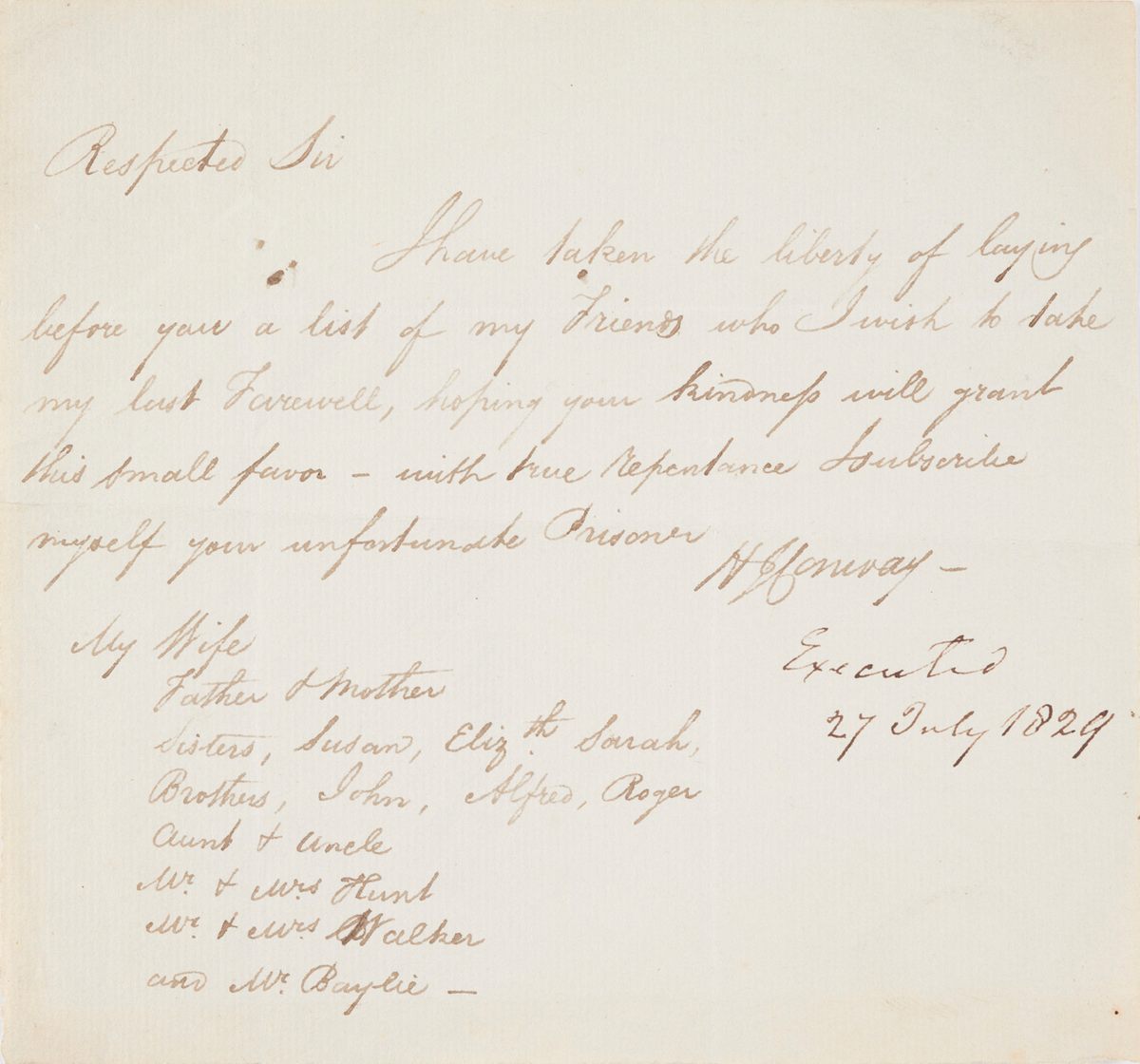

The other artifacts include letters from Newgate Prison inmates. Henry Conway (19 years old) was sentenced to death in 1829 for forgery. He also included a list of family and friends that he hoped would be able to visit him before his execution in July 1829. Jeater believes he was able to visit them. In ExecutionsVisitors can also hear the letters being read aloud at Pentonville Prison, London. This is an opportunity to reflect on the relationship between public executions (now considered barbaric) and the modern carceral system.

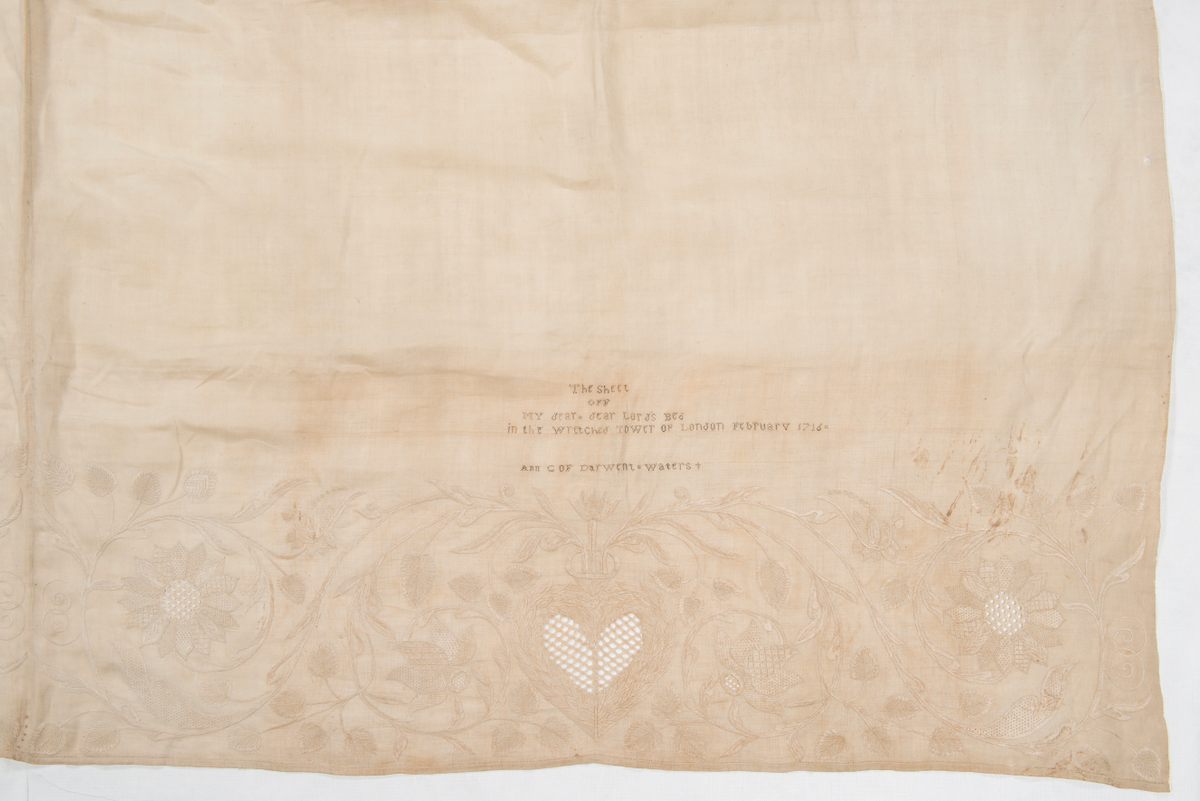

A bedsheet belonging to James Radclyffe (3rd Earl of Derwentwater) was another item that the curators found particularly moving. He was beheaded in 1716 as a result of treason. His wife Ann was allowed to stay with him in Tower of London before his death. Ann took the sheet from their marital bed and embroidered it with flowers, a heart, and a kind of epitaph: “The sheet off my dear, dear lord’s bed in the wretched Tower of London.” Upon examination, the museum discovered that Ann’s lament is sewn in human hair. Jeater believes it contains hair from both husband and wife, but further research is needed to confirm this.

Additional testing is underway for the vest that Charles I may have worn. The museum concluded that the vest’s quality and craftsmanship were generally comparable to what you would expect from a wealthy man in 17th-century England. Now, curators are working to make this even more accurate. A small piece of cloth will be radiocarbon dated, and dye analysis will take place to determine the color of the waistcoat before light damage over the years. The exhibit keeps the waistcoat in darkness until visitors press a button to briefly lighten it. This prevents further degradation. It is also being examined by experts who will help explain how it was made.

While the final results won’t be 100% conclusive, Jeater feels that the artifacts reveal the greater truth about how the public reacted to these horrific spectacles. “You could focus on numbers—the thousands executed for this crime, the hundreds executed for that crime—but then people become statistics,” she says. “We want to pull out the ordinary human stories, so people can think a bit about how it might have felt to have been in that situation.”